Es ist ein Witz, dass er den Nobelpreis nicht hat, und ich habe ihn. Ich halte Pynchon für einen der bedeutendsten lebenden Schriftsteller, weit vor Philip Roth übrigens. Ich kann doch den Nobelpreis nicht kriegen, wenn Pynchon ihn nicht hat! Das ist gegen die Naturgesetze. Ich wünsche, das festgehalten zu haben.

It is a joke he hasn’t received the Nobel prize and I have. I consider Pynchon one of the most important writers alive, much more important than Philip Roth, by the way. I cannot receive the Nobel prize as long as Pynchon hasn’t got it! That is against natural laws. That’s for the records.

Elfriede Jelinek (2004), Austrian translator of Gravity’s Rainbow; all translations in this post by Utz Klöppelt

Elfriede Jelinek’s Admiration for Thomas Pynchon

If Pynchon is really interested in receiving the Nobel Prize for Literature is in doubt. The last award Pynchon was granted was the inaugural biennial Christopher Lightfoot Walker Award (2018) by the American Academy of Arts and Letters (more in an earlier blog post of mine).

In Gravity’s Rainbow he has the narrator say:

All the oil money taken out of these fields [the oil fields of Baku, U. K.] by the Nobels has gone into Nobel Prizes. (Pynchon 1973: 354)

But that’s another story. Jelinek does, however, express her admiration for Pynchon for good reasons.

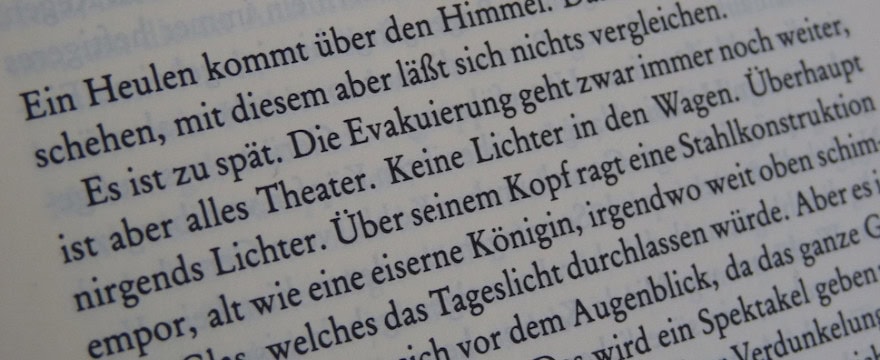

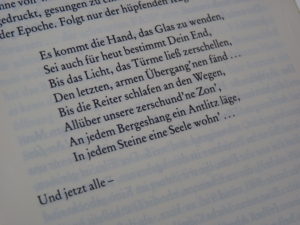

A famous writer herself, she is the Austrian translator of Gravity’s Rainbow (in cooperation with Thomas Piltz), Die Enden der Parabel – thus the German version of the title. (Pynchon 1981)

In her novel Neid (2008), “Envy”, written on and for the Internet, not published as a book, Jelinek has her narrator express admiration for his or her “personal god P.”:

[…, U. K.] die Entropie steigt schwindelerregend an, es gibt von ein und demselben immer nur dasselbe, und zwar überall, das Maß der Unordnung, welches wir zur Tarnung Ordnung nennen, steigt immer, es ist alles aufgeräumt, auch die Menschen sinds [sic, U. K.] inzwischen, denn die Frauen können immer noch putzen gehen, selbst wenn sie sonst gar nichts mehr können und nie etwas andres konnten, während der Tourist ganz andre, aber ebenfalls vorindustrielle Techniken anwendet, um bloß zum Spaß hier Erz zu schmelzen und zu einer Statue von wunderbar antikisch-ebenmäßiger Scheußlichkeit zu formen, die sofort zu ihrer eigenen Salzsäule erstarren würde, hielte man ihr einen Spiegel vor, ja, wahre Schönheit ist echt ein Hammer, nein, es ist da eindeutig eine Eisensäule entstanden, sogar ein sprechender Hund könnte es, der sein Bein immer woanders hebt: diese grenzenlose Mobilität auszuprobieren, ein Hund (Pugnax), der Henry James liest, Rr Rff-rff Rr-rr-rff-rrf-rrf,

bitte um Entschuldigung, das ist nicht von mir, leider, das ist vom MEISTER, meinem persönlichen Gott P., persönlich.

[… U. K.] entropy increases, making you dizzy,, of the one and the same there only exists one and the same, everywhere, that is, the degree of chaos, which we camouflage as order, always increases, everything is in order, by now even us human beings are in order, women can still go and clean up, even if they cannot do anything else anymore and have never been able to do anything else, while the tourist employs totally different, but also pre-industrial techniques in order to melt ore, just for fun, and form a statue of fascinating, antique-like, well-proportioned ugliness, which would freeze to its own pillar of salt immediately if it had to face a mirror, true beauty is a hammer, indeed, no, what has definitely emerged is a pillar of iron, even a speaking dog could do that, always raising its leg somewhere else: acting out this limitless mobility, a dog (Pugnax) reading Henry James, Rr Rff-rff Rr-rr-rff-rrf-rrf,

I beg your pardon, it’s not by me, unfortunately, it’s by the MASTER, my personal god P., personally. (Jelinek 2008: chapter 4c, sections 41f.)

In this passage Jelinek refers to Pugnax from Thomas Pynchon’s opening chapter of Against the Day:

‘Rr Rff-rff Rr-rr-rff-rrf-rrf,’ replied Pugnax without looking up … (Pynchon 2006: 5)

Her take on the question of beauty and her admiration for „P.“ above (2008) marks a long-term engagement with Pynchon, which had started with her reading of V. and her translation of Gravity’s Rainbow into German.

But – does Elfriede Jelinek offer unique insights into Gravity’s Rainbow from her reader and translator’s perspective?

A Selection of Jelinek’s Approaches to Gravity’s Rainbow

In the article “kein licht am ende des tunnels” (1976) for the Austrian magazine manuskripte Jelinek offers her reading of Gravity’s Rainbow, pointing out different themes and approaches to the reader when dealing with the novel (Jelinek 1976). Even though Jelinek might take a different stance to reading Gravity’s Rainbow today, some of her ideas are still worth considering:

The Title: “Die Enden der Parabel”

Whereas many translations bear the direct translation of the original title, e. g. El arco iris de gravedad for the Spanish version, Jelinek chose to stick with the German word “Parabel” and with “Die Enden der Parabel” she offers mindful associations:

- “Parabel” is the German word for “parabola”, e. g. the form of the path the rocket takes between two points, or, with regard to the rainbow, the illusionary play of light and falling rain, not so much a parabola, but similar in form.

- At the same time, “Parabel” means “parable” – denoting the literary form of the simile, “Gleichnis” in German, generating associations with the literary form.

- Jelinek, however, proclaims the end / the endings of the parable, or, respectively, refers to the two points of the path the rocket follows: the starting point and the end. Combine that idea with a) the meaning of “Parabel” as “parabola” and b), at the same time, to “parable” (Jelinek 1976: 36f.)!

Apocalypse Now? Gravitating towards Destruction and Death

There are numerous critics who have dealt with this topic (See e. g. Herman / Weisenburger 2013: esp. Chapter 1). Jelinek reads Gravity’s Rainbow as portraying a world in decadence, in the Freudian sense gravitating towards death – with America being a part of it:

pynchon betrachtet amerika konsequent als teil dieser sterbenden kultur […].

thus pynchon regards america as being a part of this dying culture […]. (Jelinek 1976: 37)

The Quest: Slothrop – Seeker of Truth

Jelinek sees Slothrop moving through the novel like a pawn, lost in the game of chess that is the Second World War:

unser tyrone slothrop wandert also […] durch den roman, wie ein bauer, der im schachspiel des 2. weltkriegs abhanden gekommen ist. (Jelinek 1976: 37)

Many of Jelinek’s thoughts on Slothrop are nothing less than a mere summary of the plot. Her reading experience and interpretation when it comes to his dissolution, however, are worth considering. She thinks of Slothrop becoming something like a magnetic field:

jene figur […] wird plötzlich entpersönlicht, wird zu etwas wie einem magnetfeld und löst sich auf.

That figure suddenly being de-personalized becomes something like a magnetic field und dissolves. (Jelinek 1976: 37)

Jelinek also ponders Slothrop’s status as protagonist or acting persona of the novel. “Sloth” indicates that he is passive rather than active, that he reacts rather than acts – reacts to stimuli or indications in some papers giving him reason and motive again to wander through the “Zone”.

The Military-Industrial Complex Plotting History

According to Jelinek Gravity’s Rainbow, or, Pynchon, as she has it, among other approaches, interprets the 20th century with its wars, with its destruction and death as being plotted by military and industrial cartels and – seemingly – a gigantic conspiracy.

“It’s all theatre …” – Jelinek sees Slothrop as the one who realizes that there has never been a political war. It was all meant to distract people from the real thing: money, the military-industrial cartel in turn being influenced by the logic of technology. (Jelinek 1976: 42)

“kein licht am ende des tunnels” – A Tragedy

Jelinek calls the novel a “tragedy”, in which characters have nothing to do anymore but to be moved by their own phantasies, cartels by the needs of technology and the logic of capitalism. (Jelinek 1976: 42)

What about the “conditio humana” suggested by the novel? Jelinek reads it as being tragic – a labyrinth without an exit.

There are signs everywhere – like “welke Blätter”, “withered leaves” (Jelinek 1976: 44)- all quests, however, for power, for truth, for love end in destruction or in dead end streets.

“kein licht am ende des tunnels” – according to Jelinek, man in Pynchon’s story moves through a tunnel without light at its end.

Further Reading

- Herman, Luc and Steven Weisenburger (2013). Gravity’s Rainbow, Domination, and Freedom, Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press.

- Jelinek, Elfriede (1976). “kein licht am ende des tunnels”, manuskripte 52, 36-44.

- Jelinek, Elfriede (2004). “Der Nobelpreis muß an mir vorüberziehen,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 8.11.2004, URL: https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/elfriede-jelinek-der-nobelpreis-muss-an-mir-vorueberziehen-1195180-p2.html (Last seen: March 5, 2019).

- Jelinek, Elfriede (2008). Neid, URL: http://www.elfriedejelinek.com (Last seen: March 5, 2019).

- Pynchon, Thomas (1973). Gravity’s Rainbow, New York et al.: The Penguin Press.

- Pynchon, Thomas (1981). Die Enden der Parabel, translated by Elfriede Jelinek and Thomas Piltz, Reinbek bei Hamburg; Rowohlt Verlag.

- Pynchon, Thomas (2006). Against the Day, London: Jonathan Cape.

Credits

- Featured image for the blog post: First sentences of Gravity’s Rainbow (German version) © Thomas Pynchon, Die Enden der Parabel, Deutsch von Elfriede Jelinek and Thomas Piltz, Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt Verlag; 1981 (2000 edition), photography by Utz Klöppelt | Reading Pynchon, March 5, 2019.

- Cover of the German translation of Gravity’s Rainbow © By Walter Hellmann; Thomas Pynchon, Die Enden der Parabel, Deutsch von Elfriede Jelinek and Thomas Piltz, Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt Verlag; 1981 (2000 edition); photograph by Utz Klöppelt | Reading Pynchon, March 5, 2019.

- Last words in Gravity’s Rainbow by Thomas Pynchon (German translation by Elfriede Jelinek and Thomas Piltz) © Thomas Pynchon, Die Enden der Parabel, Deutsch von Elfriede Jelinek and Thomas Piltz, Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt Verlag; 1981 (2000 edition); photograph by Utz Klöppelt | Reading Pynchon, March 5, 2019.